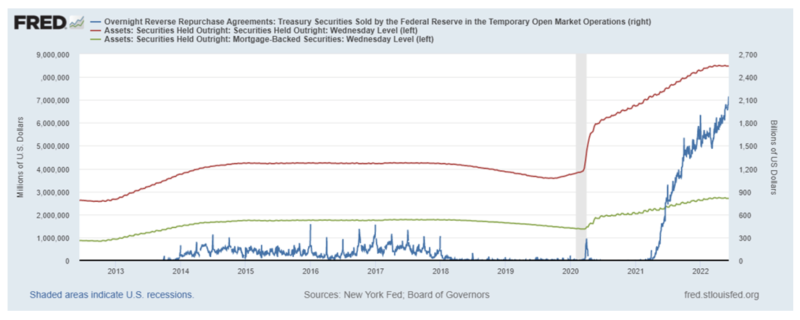

This excellent chart was featured in a commentary written by my friend Christopher Whalen.

Here’s the link to his analysis: “QT & Powell's Liquidity Trap,” https://www.theinstitutionalriskanalyst.com/post/qt-powell-s-liquidity-trap.

Let’s add a couple of points to the analysis. As Chris notes, the duration of the Fed’s mortgage-backed portfolio has lengthened enormously since the positions were originally acquired by the Fed. Why? Because those mortgages are at very low interest rates; hence, the recent rise in rates means the amount of refinancing has dropped to minimal levels. And some of the underlying mortgages are assignable, so they are not paid off if there is a transfer of ownership. In other words, these are now very-long-term securities at low interest rates, and they are likely to be on the Fed’s balance sheet for a very long time.

Of course, the Fed could sell them and recognize a loss. But we must remember that those sales would pile onto an already weak fixed-income market and depress all fixed-income prices (raising market yields higher). Remember that the Fed does not mark its portfolio to market on its official statements although it does publish estimated market prices of its holdings. That data can be found on the NY Fed’s website. Were the Fed to recognize the loss by selling, the loss would then become a payable from the reserve banks as a long-term liability. We don’t expect that to happen.

The Fed could also create a CMO and hold the mortgages with the CMO offsetting the holdings. That would be a way to transfer the holdings to the market at today’s lower prices while the mortgages officially remain holdings of the Fed. A Maiden Lane-type of CMO could be organized. Chris Whalen and I have discussed this approach. The Fed folks are knowledgeable and may be studying the option. There has been no official commitment to use the CMO technique as an exit strategy for the $2 trillion in mortgages. We shall see if it happens in the future.

For now, the most likely outcome is that the $2 trillion of mortgages are embedded in the Fed’s portfolio for a lot of years. And that’s the way it is.

Here’s the other side of that trade. To acquire those mortgages, the Fed had to create the monetary liability to offset the asset purchase. That money is now mostly parked in overnight repo. We see it on Chris's chart.

To summarize, the Fed has $2 trillion of very-long-duration assets on its balance sheet and $2 trillion of the shortest duration, as the counterweight, in overnight-duration liability. Note that the liability side requires collateral. The usual collateral is composed of very short-term Treasury bills. Also note that the lunacy of politicians bent on playing out brinksmanship in the debt-limit charade can drastically impact the issuance of short-term Treasury bills. Politicians are already creating market distortions. Market agents are now positioning their portfolios to avoid a possible clash with the expected “X-date”. X-date is the term for the day when the US Treasury runs out of money and cannot make a payment.

Those distortions mean rising pressures for collateral to secure the overnight repo. Our elected members of the national legislature are in the midst of playing with a financial fire now and most of them do not understand it. Try this: think of the Members of Congress you read about or hear on TV. How many of them really understand the damage they are doing to the country every day? In my opinion, very few grasp that brinksmanship has a tangible cost. We are the ones who pay that cost. I do not believe the Fed will allow a repo failure. But it has only limited ability to deal with the collateral shortage if the US Treasury cannot issue bills.

Let’s move to the bond market side.

The financial markets have witnessed the withdrawal of $2 trillion of long-duration fixed-income securities from the market and simultaneously witnessed the transfer of the very short duration of overnight repo to the market. The technical impact is that market agents were able to transfer duration risk to the Fed.

Good for those who did it at the time. But now that game has ended.

A large duration transfer of risk from the market to the central bank happens only once. Then the chickens come home to roost. That is a process we are starting to see in markets. It results in unusual pricing because the duration transfer distorts price discovery in the markets.

We will offer an example.

The longer-term US Treasury bond (30 years) is trading at an interest rate of about 4% as this commentary is written. At the same time, a very-high-grade tax-free housing bond is trading at a yield of about 5% and that bond is secured by a basket of mortgages, and those mortgages are similar to the ones held by the Fed on its balance sheet when it comes to their creditworthiness. In other words, a direct and taxable claim of long duration, backed by the US Treasury, yields 4%, while a passthrough claim that is tax-free and secured by the same US Treasury and is now yielding 5%. This is partially a result of the duration transfer we described above.

The housing authority tax-free bond reflects what new-issue housing finance is pricing now in the current market climate. It demonstrates the impact that has occurred after the Fed bought the mortgages over many years of accumulation. We see those years in the Whalen chart. The long-term Treasury bond yield reflects a market where the duration still resides on the Fed’s balance sheet.

What happens next?

Maybe Goldilocks will prevail, inflation will abruptly decline to 2%, and the Fed will stop tightening policy interest rates and cease QT. But we don’t expect that.

Instead, we expect the market to engage in a repricing of the duration risk as the Fed’s activity of past years wanes in impact and as the passage of time powers the adjustment process. That means higher mortgage interest rates are coming. If the Fed sells its mortgages, this situation gets a lot worse. That is why we don’t expect it to happen.

When the Fed expanded its balance sheet by trillions, it also lengthened the duration of the holdings. By using mortgages, the Fed took on the additional risk of slowing prepayment speeds resulting from rising interest rates. Now we have the results.

When available, we are buyers of 5% high-grade tax-free long maturity bonds after we do the needed research about credit. We must warn folks to beware any intervention into the credit rating work by political interventionists who want to restructure the credit mechanism. Politics interferes with price discovery. Be careful.

We are not buyers of the 4% 30-year Treasury bond. Why should our client receive 4% secured by a US government pledge when you can receive 5% backed by a similar credit structure? And the 5% is tax-free, so there is an implied market cushioning of risk when and if the tax-free-to-taxable rate mechanism is restored to normalcy. Normalcy means tax-free yields are lower than taxable yields, not higher.

That is why some clients may see a tax-free bond in an account that is not paying taxes.

Anyone interested in the mechanics and details of our tax-free bond management structure may email me for them.

David R. Kotok

Chairman & Chief Investment Officer

Email | Bio

Links to other websites or electronic media controlled or offered by Third-Parties (non-affiliates of Cumberland Advisors) are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Cumberland Advisors has no control over such websites, does not recommend or endorse any opinions, ideas, products, information, or content of such sites, and makes no warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, reliability or suitability of their content. Cumberland Advisors hereby disclaims liability for any information, materials, products or services posted or offered at any of the Third-Party websites. The Third-Party may have a privacy and/or security policy different from that of Cumberland Advisors. Therefore, please refer to the specific privacy and security policies of the Third-Party when accessing their websites.

Cumberland Advisors Market Commentaries offer insights and analysis on upcoming, important economic issues that potentially impact global financial markets. Our team shares their thinking on global economic developments, market news and other factors that often influence investment opportunities and strategies.